Ismael Rafols, Centre for Science and Technology Studies (CWTS), Leiden University and Science Policy Research Unit (SPRU), University of Sussex

The shift in R&D goals towards the SDGs is driving demand for new S&T indicators…

The shift in S&T policy from a focus on research quality (or ‘excellence’) towards societal impact has led to a demand for new S&T indicators that capture the contributions of research to society, in particular those aligned with SDGs. The use of the new ‘impact’ indicators would help monitoring if (and which) research organisations are aligning their research towards certain SDGs.

Responding to these demands, data providers, consultancies and university analysts are rapidly developing methods to map projects or publications related to specific SDGs. These ‘mappings’ do not analyse the actual impact of research, but hope to capture instead if research is directed towards problems or technologies that can potentially contribute to improving sustainability and wellbeing.

…but indicators on the contributions of science on the SDGs are not (yet) robust

Yet this quick surge of new methods raises new questions about the robustness of the mappings and indicators produced, and old questions about the effects of using questionable indicators in policy making. The misuse of indicators and rankings in research evaluation has been one of the key debates in science policy this last decade, as highlighted by initiatives such as the San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment (DORA), the Leiden Manifesto or The Metric Tide report in the UK context.

Indeed, the first publicly available analysis of SDG impact, released recently by the Times Higher Education (THE), should be a motive for serious alarm. For almost two decades, the THE has offered a controversial ranking of universities according to ‘excellence’. This last May it has produced a new ranking of universities according to an equally questionable composite indicator that arbitrarily adds up dimensions of unclear relevance. For example, the indicator of the impact on health (SDG3) of a university depends on the one hand on its relative specialisation on health – as captured, e.g. by the proportion of papers related to health (10% of total weight), and on the other hand on the proportion of health graduates (34.6%). But the weight is also based on (self-reported) university policies such as care provided by the university, e.g. free sexual and reproductive health services for students (8.6%) or community access to sports facilities (4%). This indicator is likely to cause more confusion than clarity and it is potentially harmful as it mystifies university policies for the SDGs.

The relative specialisation on health captured by the proportion of papers related to health in the THE ranking is partly supported by an Elsevier analysis of the publications that are related to the SDGs – which might seem more reliable than those based on data self-reported by universities.

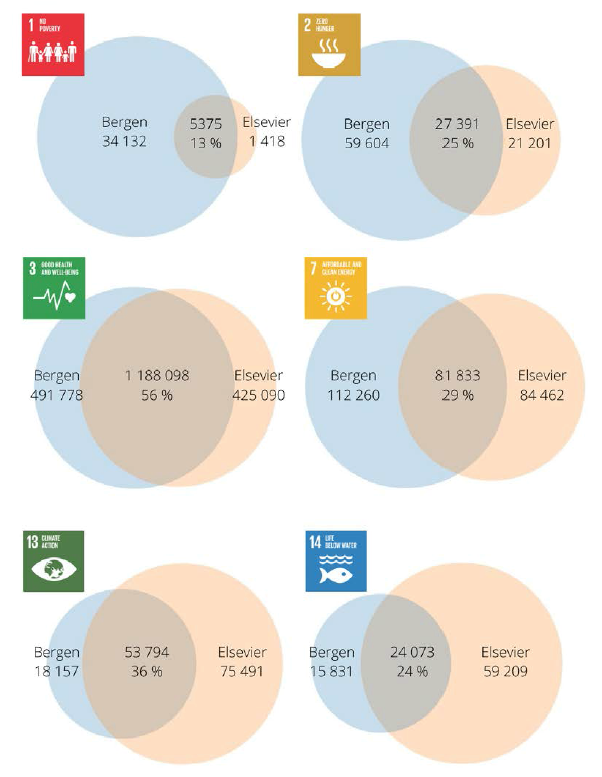

However, mapping publications to the SDGs is not as straightforward as it might seem. An article published last month by a team at the University of Bergen (see Armitage et al., 2020) sounded the alarm by showing that slightly different methods may produce extremely different results. When comparing the papers related to SDGs retrieved with their own analysis with those by Elsevier, they found that there is astonishingly little overlap – in most SDGs only around 20-30% as illustrated in Figure 1. The differences also affected the rankings of countries’ contributions to the SDGs. The Bergen team concluded that ‘currently available SDG rankings and tools should be used with caution at their current stage of development.’

Figure 1. Comparison between the Bergen and Elsevier approaches to mapping SDG-related publications. Based on Web of Science Core collection, 2015-2018. Source: Armitage et al. (2020)

Why are mappings of publications to SDGs so different? Lack of direct relation between science and SDGs

Perhaps we should not be surprised that different methods yield so different results. The SDGs refer to policy goals about sustainability in multiple dimensions – ending poverty, improving health, achieving gender equality, preserving the natural environment, et cetera. Science and innovation studies have shown that the contributions of research to societies are often unexpected and highly dependent on the local social contexts in which knowledges are created and used.

Nevertheless, most research is funded according to the expectations of the type of societal benefits that it may generate – and thus one can try to map these expectations or promises according to the language used in the (titles and abstracts of) projects and articles. Unfortunately, the expected social contributions are often not made explicit in these technical documents because the experts reading them are assumed to see the potential value.

As a consequence, the process of mapping projects or articles to the SDGs is ineluctably carried out through an interpretative process that ‘translates’ (or attempts to link) scientific discourse into potential outcomes. Of course, such translation is dependent on the analysts’ understandings of science and the SDGs. There is consensus on some of these understandings. For example most analysts would agree that research on malaria is important for achieving global health. However, other translations are highly contested: should nuclear (either fission or fusion) research be seen as a contribution to clean and affordable energy? Should all educational research be counted as contribution to the SDG on ‘quality education’?

Furthermore, in a number of SDGs such as gender equity (SDG 5) or reduced inequalities (SDG 10), there is a lot of ambiguity on the potential contributions. In particular, there is relatively little research specifically on these issues in comparison to the research with outcomes affecting gender relations and inequalities.

Another challenge of these mappings is that the databases used for analysis are not comprehensive, having a much larger coverage of certain fields and countries (See Chapter 5 in Chavarro, 2017). This is particularly problematic when analysing research of the Global South.

In summary, there are many societal problems where there is lack of consensus and ambiguities, and in these cases, the mappings will depend on the particular interpretation of the SDGs that the mapping methods implicitly adopt.

A plurality of SDG mapping methodologies

It follows from the previous discussion that different analyses carry out different ‘translations’ of the SDGs into science through the choice of different methodologies. The study by Clarivate (2019) is based on a core set of articles that mention ‘Sustainable Development Goals’ – thus it is related to research areas with an explicit SDG discourse.

The approaches developed by Bergen University, Elsevier, the Aurora Network and SIRIS Academic are based on searching for strings of keywords, in particular keywords found in the UN SDGs targets or other relevant policy documents. These searches are then enriched differently in each case. The hypothesis of this ‘translation’ is that publications or projects containing these keywords are those best aligned with the UN SDG discourse. The question is then where should the line be drawn. For example, why in some lists zika virus is included in the list of health SDG3, but not the closely related dengue virus, with a much higher disease burden?

An alternative approach being developed at NESTA and Dimensions uses policy documents and keywords to train machine learning algorithms in order to identify articles related to the SDGs instead of creating a list of keywords to search the articles. The downside of this approach is that is it a black box regarding the preferences (or biases) of the machine learning algorithms.

Comparisons as a pragmatic way forward

In the face of this plurality of approaches potentially yielding disparate results, the STRINGS project aims to be a space for constructive discussion and comparison across different methodologies. A comparison between methods will help in finding out to which extent there is consensus or dissensus in the mappings of various SDGs.

To this purpose, in collaboration with the Data Intensive Science Centre at the University of Sussex (DISCUS), on July 23-27 we have carried out a hackathon focussed on retrieving publications related to clean energy research (SDG 7) (to be reported). We have also organised a workshop to discuss the results obtained by the different teams mentioned above with the various methodologies, and how each methodology might capture a particular ‘translation’ or understanding of the SDGs. As proposed by the Bergen team, this comparison ‘will allow institutions to compare different approaches, better understand where rankings come from, and evaluate how well a specific tool might work’ for specific contexts and purposes.

Disclaimer

The discussion in this blog builds on ongoing work carried out by the STRINGS project. It presents my personal view (rather than the project’s) following my engagement debates on the use of indicators in policy and evaluation, for example a recent participation in an EC Expert Group on ‘Indicators for open science’.

Leave A Comment